‘One Battle After Another’ Review: P.T. Anderson’s Mesmerizing Vision

“One Battle After Another,” the turbulently powerful and enveloping new movie written and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson, is set in an America that’s become a fascist police state: a place where immigrants are rounded up en masse and placed in detention centers, where the police and the military have fused into an implacable authoritarian force, where a hidden cabal of Christian nationalists plan the future from a star chamber, and where a group of ragtag revolutionary guerrillas attempt to disrupt the regime through random bombings and bank robberies. “One Battle After Another” is a movie that taps down into the fierce urgency of now; it gives you a chill that’s also a wake-up call. Yet when you hear the movie described, it can sound rather aggressive in its dystopian topicality, like a bombs-away, knowingly over-the-top thriller-satire of where we are today and where we might be headed.

The surprise of “One Battle After Another” is that while it speaks with a big vision to the danger and anxiety of our moment, it’s also a drama that’s totally grounded and relatable. There’s a thematic heft to it, and the movie is often quite funny in a sidelong way, but it’s not some in-your-face didactic absurdist thing. “One Battle After Another” is a vision of a society in captivity, but it’s a movie that never loses the pulse of its humanity.

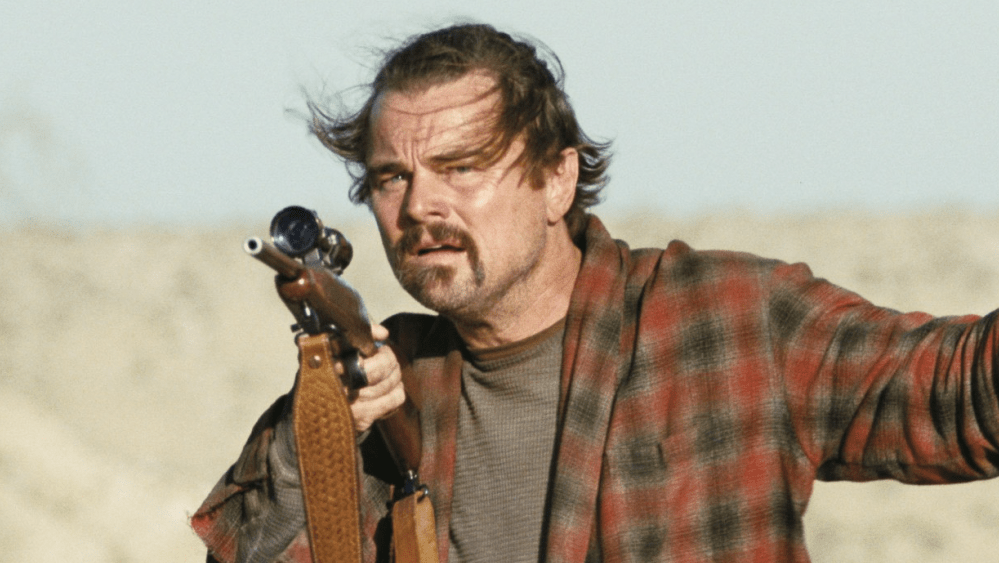

At first we think we’re going to be seeing some elevated action saga of the revolution vs. the regime. Anderson plunges the audience into the rebels’ point of view, immersing us in the recalcitrant pride and swagger of Perfidia Beverly Hills, a revolutionary leader played by Teyana Taylor with a hypnotic sneer of defiance. Perfidia’s partner, in life and revolution, is Bob Ferguson (Leonardo DiCaprio), a scruffy demolitions expert, and as they infiltrate a compound and stage an attack, which the film portrays in all its existential randomness, we may wonder how, exactly, this is going to have much impact on a monolithic government of oppression.

It isn’t. The film’s revolutionaries, who call themselves the French 75, come clothed in the take-no-prisoners rhetoric and fist-in-the-air attitude that’s been the signifier of righteous radicalism since the late ’60s. But in “One Battle After Another,” the actions of the revolutionaries look entirely quixotic — a tiny eruption of disruption, a tilting at the windmill of dictatorship.

That said, the film spooks us with the question: Is this where America is now heading? Anderson, who built “Once Battle After Another” around elements he borrowed and reworked from Thomas Pynchon’s 1990 novel “Vineland” (which is set during the Reagan era), completed the movie before Donald Trump took office in January 2025, but it’s presented as a knowing projection of what autocracy under the current administration could lead to. The film isn’t just some abstract metaphoric cinematic speculation; it’s designed to look and feel just ahead of the curve of where we’re at now. And since “Once Battle After Another” is trying to be ruthlessly authentic about how an authoritarian state works, the revolutionaries, it turns out, don’t have much of a chance. Their battle against the government is not what the movie is about.

Instead, the film sets up a perversely resonant sort of left-meets-right love triangle. There’s Bob and Perfidia, the outwardly “romantic” revolutionary outlaws. And then there’s the U.S. Army officer who succeeds in apprehending Perfidia: Col. Steven J. Lockjaw, played in a graying military fade, with some fur on top and a martinet scowl, by Sean Penn. When we hear the character’s name (Lockjaw!), it seems a cue to giggle, because it’s got such a daffy-metaphorical “Strangelove” vibe. But this is not “Strangelove,” and the key to the character is that Penn, all leathery skin and drawn features and glare of silent boiling dread, is far too great an actor to portray Lockjaw as a cartoon. He gives him a rigid set of military manners and a stern repressed energy that’s a little scary, but we also see the vulnerability he’s working hard to keep a lid on. Lockjaw lusts after Perfidia and spends a secret night with her (putting himself in a passive sexual position), and the result of their ambiguous tryst is that she becomes pregnant. This development introduces the film’s most haunting theme: that even the clashing elements of our society — warring ideological factions, citizens of different racial backgrounds locked in antagonism — are actually, underneath it all, deeply and inseparably intertwined.

Is “One Battle After Another”…a drama? Yes, but not entirely. It’s a drama pitched on the hexagonal fault line that conjoins drama and comedy and thriller and allegory and satire and social-political tragedy. It’s all those things at once, and that’s why even when what’s happening is starkly flamboyant, you can’t reduce it in your mind to something less than three dimensions. The film is dotted with close-ups, plugging us into the actors with an intimacy that keeps on giving. And Anderson, who’s credited as one of the film’s two cinematographers (along with Michael Bauman), has devised a visual style that’s mesmerizing in its flow, with lavishly detailed images that are oiled with a dark ’70s grunge. Each shot carries you along, creating an exhilarating momentum that draws us in emotionally as well.

“One Battle After Another” has the kind of twists and turns that feed the audience, giving us the childlike sensation that we have no idea what’s coming next, and that that’s the happiest way there is to watch a movie. After Perfidia gives birth to a daughter, Bob, who thinks he’s the father, undergoes a shift of loyalty: from revolution to family. (Perfidia the die-hard rebel does not.) And the way DiCaprio plays this, with a freshly awakened devotion, makes you feel just how personal the movie is. “One Battle After Another” is merciless in its depiction of totalitarian clampdown, but Anderson, who has four children with Maya Rudolph, may be more ambivalent about the ideological purity of his revolutionaries than he at first lets on.

Penn’s Col. Lockjaw, in love with Perfidia (even though she represents everything he hates), does her a favor by setting her up in an anonymous suburb as part of a witness protection program. But she’s having none of that, and escapes to Mexico. The film then cuts to 15 years later. The revolution is in tatters, and DiCaprio’s Bob, once a celebrity rebel, is now a benignly useless substance-using layabout who tries, in his shambling way, to take care of his and Perfidia’s daughter, Willa (played with a no-nonsense radiance by Chase Infiniti).

But there’s a sinister scheme afoot. Lockjaw has been invited to join the Christmas Adventurers, a secret club of white nationalists, played by actors like Tony Goldwyn and Jim Downey, who confer great privilege upon their members, but who demand (among other things) racial purity. The group’s name is obviously satirical, but is what we see going on behind their closed doors satirical? That’s for the audience to decide. I’d say that the way these creepy men talk is, at the current moment, too ominously close for comfort to what’s happening off-camera within the current American power structure. It’s a vision of the new agenda. And when Lockjaw, who will do anything to join them, discovers that they may know of his mixed-race child, he sets a kidnap plot in motion that transforms the movie’s second half into a rescue thriller of the most haphazard and exhilarating urgency, with Jonny Greenwood’s modernist musical score pacing the film like a metronome of suspense.

DiCaprio, as fine an actor as he can be, has played the aging-baby-face leading man too many times. Anderson knows that the quality that liberates DiCaprio is comedy. By having him play Bob as a dissolute stoner addict, discombobulated by his loss of faith, he humanizes DiCaprio and coaxes a great performance out of him. We’re totally keyed into Bob — his misplaced valor, his loser karma, the desperate heroics that are rooted in his scuffed decency.

The funniest moment in the movie is when Bob, calling what remains of the rebel underground, can’t remember the code-word answer to “What time is it?,” and you can feel how his increasingly impacted frustration at the nitpicking of rebel headquarters stands in for the filmmaker’s perception of everything that has gone wrong in liberal bureaucratic culture. The scene bonds us to Bob, cueing us to what a blessed ordinary soul he is. And he’s one of an ensemble of rich characters, like Benicio del Toro’s sleepy-eyed sly-dog martial-arts-instructor-turned-revolutionary-adjunct, who are trying to preserve their dream in the middle of a political nightmare. In the film’s ecstatic climactic car chase, where Anderson films the vehicles rolling up and down highway hills like something out of “Vanishing Point” as reshot by Michelangelo Antonioni, we see that Bob will go to the ends of the earth for his daughter.

“One Battle After Another” is a warning, a life-under-autocracy version of Talking Heads’ “Life During Wartime.” It’s also an action-packed allegory of how we got here. Lockjaw’s “transgression” with Perfidia Beverly Hills takes us back to the hidden comingling of the races that was there at America’s foundation — that is, the systemic rape of enslaved women by slave holders. The film suggests that the current white-nationalist movement is, in heart, an attempt to separate white and Black people as a primal way of pretending that all that never happened. And that this denial is nothing less than the key fantasy driving the new alt-right America. Bob leaves revolution in the dust to rescue his mixed-race daughter, but the movie says that what he’s doing is the real revolution: finding a family that you fight to hold together; keeping Black and white together, as they long have been; keeping hope alive, in the face of a regime that employs the stifling of hope as a ruling tactic. The movie says that out of this revolt of the everyday a greater revolution will rise.

Back in 1997, I considered myself just about the most ardent critical champion of “Boogie Nights,” the then 27-year-old Paul Thomas Anderson’s great drama set in the American porn industry — a movie that said that the change from film to video in porn embodied the paradigm shift in America from pleasure to addiction, from faith to fear. (I saw it more than 30 times.) “Magnolia” spoke to me too, but since then I have never fully connected with Anderson’s work, finding his movies, even upon repeat viewings, to be cryptic (“The Master”), didactic (“There Will Be Blood”), precious (“Punch-Drunk Love”), contrived (“Licorice Pizza”), overly tailored (“Phantom Thread”), or just plain wacked (“Inherent Vice”). “One Battle After Another” marks the first time in 26 years I’ve watched a Paul Thomas Anderson film that I felt was inviting me into its world as passionately as the film was creating it. You could say I’ve now come back to being an Anderson believer, but the way I’d put it is this: After years of overly determined theatrics, he has gone back to being a master.