Juliette Binoche on Her Directorial Debut ‘In-I In Motion’

Juliette Binoche won an Oscar for the “The English Patient;” has worked with the greatest auteurs, from Leos Carax to Abbas Kiarostami and Olivier Assayas; and has presided over Cannes and Berlin juries, among her many achievements. But in classic Juliette-Binoche style, the iconoclastic French actor didn’t take the easy route to direct her first film.

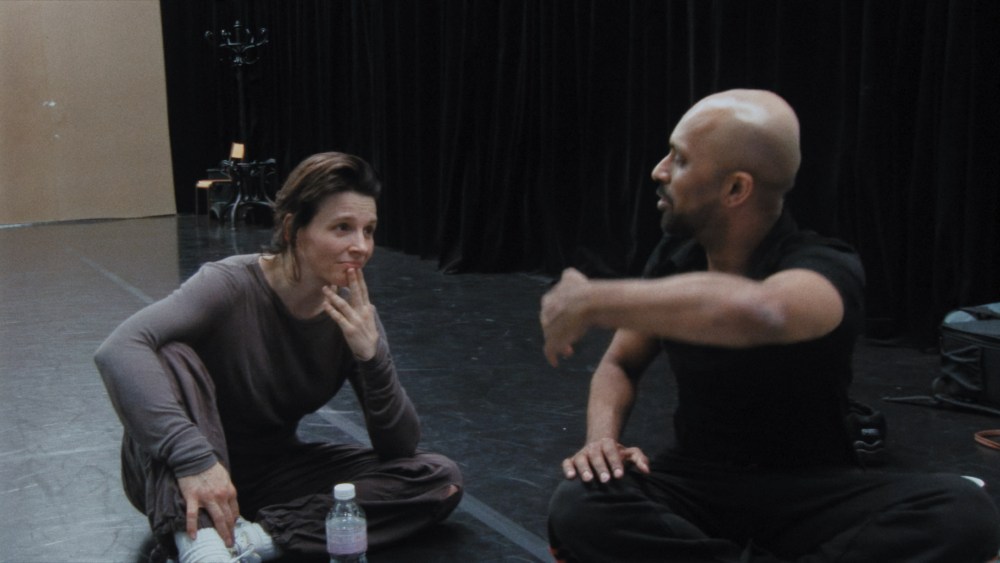

‘In-I In Motion,’ which is world premiering today at San Sebastian Film Festival, charts her chaotic, daunting and ultimately cathartic experience co-creating and performing a dance show with well-known British choreographer Akram Khan over the course of a sabbatical year and a half in 2007. It turns out that making “In-I In Motion” proved almost as excruciatingly difficult as creating the show itself, Binoche tells Variety ahead of San Sebastian, because it required her to transform 170 hours of footage, chase music rights for songs used during countless rehearsal sessions and edit the abstract material into a film. The result is a work that’s equally intellectual, political and visceral, reflecting on the nature of artistic creation, but also highlighting Binoche’s personality and taste for boundary-pushing challenges.

On paper, the story of a famous actress learning how to dance with an acclaimed choreographer could sound like the pitch of a romantic comedy, but “In-I In Motion” goes in a complete different direction as Binoche unveils her fears, revisits some traumas, as well as depicts the physical and emotional challenges she faced during the making of the show which she and Khan went on to perform 100 times around the world. Along with directing, Binoche also produced the film alongside Sébastien de Fonseca at Miao Productions, in co-production with Ola Strøm at Yggdrasil and Solène Léger at Léger Production. During our interview, Binoche also talks about how Robert Redford gave her the impulse to film the performance, and discusses the political dimension of “In-I In Motion,” and the role of artists in society.

First off, I wanted to say that I was out-of-breath just watching you dance in ‘”In-I In Motion.” It’s impressive!

Ha, I was out of breath, too!

What made you want to take a sabbatical from your busy acting career to create this show even though you were not a professional dancer?

I take some breaks, once in a while, and one of them was used to co-create this show with Akram Khan for about a year and a half altogether, or almost two years. I think it’s important to do these parentheses in order to re-nourish yourself or recontact your desire somehow and I love plunging into other worlds.

Where did the idea of this collaboration with Akram Khan come from? Did you know him?

Actually, it all started as I was being massaged by Su-Man Hsu whom you can see in the film because she was our rehearsal director. She does a lot of different things and one of them is shiatsu massages. So I was shooting in London and she was massaging me and it was so painful. And as she planted her elbow into my back, she said, “Do you want to dance?” And out of the blue, I said, “Yes.” And so she invited me to see Akram Khan’s show at the time that her husband, Farooq Chaudhry, was producing. So I saw the show and found it mesmerizing. And at the end, they made me meet Akram, and they said, “Do you want to improvise for two or three days, see if you can do something together?” And we did that. And we said, “We enjoy each other’s company. And it was a good experience.” so we said, “Okay, let’s see each other in two years time,” because he was touring and I was shooting. And eventually we got into each other’s world. And it was fascinating, but at the same time, so difficult because to go into another person’s craft. It takes courage. There are moments where you’re totally lost and your body is not ready to go. For Akram, it was more emotionally, where he wasn’t ready to go there. So it’s like being on the edge of a cliff and seeing a huge void in front of you and behind you. And you just got to jump and do it regularly because being constant really makes the craft and the possibility come true.

And it worked out well since you toured ‘In-I In Motion‘ in 100 cities! At what point did you decide to film the show?

Yes, we were touring, and we went to a lot of different continents for many months. After that we arrived in New York City, and we danced at the BAM Theater. And Robin Redford came to my dressing room, and he said to me, “You’ve got to film this piece.” And he was so intense and passionate about it that I said, “Yes, I was thinking about it.”

But we only had one more month touring, I thought, “how am I going to handle this? I’ve got to make it happen!” And I had no production, no idea how to handle it, and whether I was going to be able to put it together one day. And it turns out my sister had come to the rehearsing room and I asked her if she could film seven shows on different angles, and she did!

How did you finance this directorial debut?

I had a Norwegian investor, Ola Strøm, who came to me with his partner, Solène Léger, and they asked me if I had a project I’d like to do because they wanted to support me. And I said, “Well, I have this thing that is in my drawer, and I’m dreaming that one day I’ll take the time to do it.” And Since the meeting in Cannes, it took two years because digitizing the tapes were already a big thing. And as we were rehearsing, we would put some different music to see where it was going to take us, and obtaining the rights to those songs was also so much work. We also had 170 hours of footage!

Did you feel like giving up on this film at some point?

Well, sometimes I was very happy with something, and at other moments I was desperate because I just felt, “This is bullshit. This is going nowhere.” There were bad days and good days. So it took a while. I started to work with one editor, and then the second one came afterwards. And then the editor assistant at the end helped me because I still was working on the beginning. The first cut was nine hours. And from there, I said, “Okay, how am I going to handle this?” I had to cut down and made pictures of each scene. It helped me because I could visualize the film. Before, it felt abstract and the visualization of the scenes really was key to me.

How transformative was the experience of creating this dance performance in your life and career?

I think that after this experience, I would say I was less frightened of taking risks. It really brought me to the edge of fear. Every night I thought I was not going to survive this show because it was so demanding physically and emotionally. It was both. Usually as actors, sometimes you can do physical things, but the combination of both is very rare. And in this show we created, it was both. And I felt like I wasn’t going to survive, really. That was the feeling every night.

You ended up not only co-creating the choreography but also writing most of the dialogue/monologue which is politically charged.

Well, I don’t think it was rationalized. I think it came from my life at the time, and probably was a little bit in advance from my time. As a young girl, I fell in love with a man while watching “Casanova.” He was a guy seated in front of me who I couldn’t even see. But then it took me on a journey of wanting to have him. And so we started the story like this. It’s a funny theme knowing that we’re in the #MeToo world now, that it was actually the young girl I was who was initiating this need of love. And so from that point, we developed the story. Then my character in the show breaks when she’s attacked by the man who wants to strangle her. It happened in my life as well. So we were going through some very personal subject matters that are spoken about now.

Akram Khan, as well, talks about his own traumas in ‘In-I In Motion.’

Yes, he’s talking also about the deep betrayal he felt as a young boy, and we see in the show that his father was witnessing all this and probably arranged it. He didn’t want to keep it in the show because his father was alive still at the time and he probably didn’t want to expose him. But still, it shows a little boy who’s in a Muslim environment, and and who has been betrayed and horribly treated. It came all together as we were doing it. I don’t think Akram wanted to have a show about a relationship. I don’t think it was really his purpose. But seeing me with this need of understanding what my life was about at that moment, made him accept it.

Do you want to direct an other film since you enjoy being involved in the creative process?

Of course. At the same time, I cannot plan my life. Life is more mysterious than that. And I just love that the fact I was able to find these two years in my life. And I did a play and a film, but I managed to concentrate on that. It felt genuine. But at the same time as an actor, you’re in the middle of creation, and you co-create in a way.

But as an actor, you’re dependent on the desire of a filmmaker. You don’t have that much control, do you?

It’s really 50/50 when we’re on set and actually, I’ve heard directors who hate the shooting time because somehow the actor has more power than they do, since they embody what they wrote, and they’re depending on their sensitivity, on their understanding, intelligence, emotions… So the co-dependency is very strong. After that, in the editing room, it’s another story. But if the actor is not happy with the editing, he may say, “Fuck you. I won’t go around the world and do promotion.” Do you see what I’m saying? So there’s a co-dependency, definitely.

You served on the Berlin jury a few years ago and gave the Golden Bear to the Israeli filmmaker Nadav Lapid for “Synonym.” He’s worried right now about the pressures from the Israeli government on artists who are becoming increasingly isolated.

It’s in the history of cinema, when you see Eisenstein, who couldn’t finish his last film because it was in the hands of Stalin. And it’s part of what it is to be an artist is to be a resistant. And when you have resistance, it means that a society is healthy. It means that not everybody think the same way. Not everybody is going in the same rules. You have to be independent in the way you’re feeling and thinking. And it’s uniting each other to be different. I think it’s a very necessary action to be thinking, to be putting in question the status quo. Artists are there to be not established, but to be who they are.

Nadav Lapid, like other Israeli artists, are also concerned about the call for boycott and how it may scrap their chances of getting into festivals again.

Nadav is such a strong artist. I don’t think he should worry too much. He’s an amazing director, and he has his own point of view, and we need that as well. But I don’t think he’ll be refused. I think at Cannes there were issues, and I didn’t really go into it because it was not my place. And of course, he was frustrated not to be in competition. But you have to be patient also when you have as a director. You really have to follow your road and what you feel, what you think, and go for it. And maybe he’ll do a smaller film that is less expensive, who knows? But he has such talent. He’s quite incredible. I’m fascinated his talent. He asked me this summer to write a little preface for his book that’s coming up so I watched all his films, and I can confirm that he’s very talented.

And this year your Cannes jury gave the Palme d’Or to Jafar Panahi who is shortlisted to represent France at the Oscars (the interview was conducted before Panahi was chosen as the official French submission)?

It’s wonderful. It should be on the Iranian list, but if it’s the French list, let’s go for it.

It can’t be on the Iranian list, unfortunately.

One day maybe!