Juliette Binoche’s Candid Dance Documentary

Of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, the screen’s most celebrated dance partners, Katharine Hepburn is famously said to have declared that he gave her class, while she gave him sex appeal. Juliette Binoche and Akram Khan each have both those qualities in spades, so what did they stand to gain from teaming up for a terpsichorean collaboration on the London stage? By 2007, the Oscar-winning French actor and the royally honored British dancer-choreographer had reached the summits of their respective professions — but while both were accomplished performers, Binoche was no professional dancer, while Khan wasn’t a dramatic actor. Unveiled at the U.K.’s National Theater in September 2008, the hybrid stage piece “In-I” was the striking result of a mutual effort to train each other in those disciplines; 17 years later, the Binoche-directed documentary “In-I In Motion” preserves it in her favored medium.

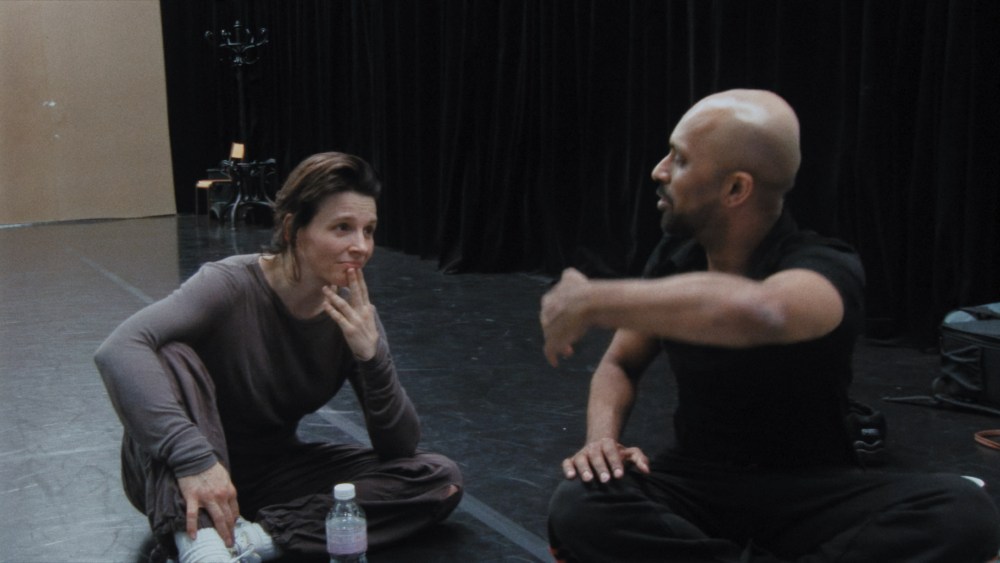

This is not a reflective work. Assembled wholly from ample studio rehearsal footage and vivid live recording of the finished stage production, “In-I In Motion” is free of voiceover, interviews or any kind of framing commentary to establish how Binoche and Khan, this far out from their unlikely experiment, now perceive the outcome and what they learned from it. Rather, the documentary affords viewers raw access to the creation process, and the rare fascination of watching two leading artists at times out of their depth, figuring out new dimensions to their craft on the hoof, so to speak.

At 156 minutes, Binoche’s film doesn’t short-sell the depth and difficulty of that process, and demands a fair bit of commitment from the viewer too. Kicking off its festival run at San Sebastian, the doc is primarily of interest to dance buffs and devotees of both performers, but may wind up courting a subset of the audience for such crossover theater-cinema events as the National Theater’s popular NT Live releases. One does wonder why Binoche, who officially marks her film directing debut with this one-off specialty item, waited this long to assemble it for the screen, though perhaps the doc benefits from some critical distance. It’s clear she regards “In-I,” which received mixed reviews at the time, as a major achievement in her ongoing self-education as an actor, but its divisive affectations are plainly presented in this format.

It’s a simply structured film of two halves, the first documenting months of rehearsals for the project (mostly in bare, black-draped dance studios) while the second presents the final 70-minute piece in its propulsive, moodily lit entirety: process and payoff, work and play. There are no onscreen dates to mark the passage of time, though we feel it substantially in the rehearsal portion, which progresses from initial, airily conceptual ideation to far more practical, particular obstacles as opening night looms: The film wrings more drama and farce than you might expect from the tricky engineering of a hidden seat to produce a floating-in-mid-air effect for Binoche’s climactic solilioquy. (Any theater directors watching may find themselves breaking into a cold sweat.)

The piece itself is quite simple, tracing the arc of a love affair from initial infatuation to bitterly extended breakup, though it takes some time to gauge the shape of it from the disarranged fragments we see in the studio — strident scraps of argument and isolated, heated physical confrontations, variously steered and tempered by famed American acting coach Susan Batson and movement director Su-Man Hsu. The film gains nerve and intrigue from the palpable exhaustion — physical and emotional — in both performers at points in these rehearsals.

That fraying can bring about their most immediate work, as in Khan’s tackling of a vulnerable monologue centered on racial identity and insecurity, or their most undisciplined: It’s often Binoche’s big, dirty laugh that breaks the tension of a movement or scene that just isn’t coming together. Tellingly, the DP for all this material is Binoche’s sister Marion Stalens: Trust and intimacy are operative words in this candid portion of the project, during which the performers are permitted to fail and flail, and we’re permitted to watch them do so.

The final staging, of course, is an altogether more polished affair, enhanced by a camera that moves with the stars as they glide, bound and tumble in and out of love. It’s rather a cinematic work even without the camera’ participation, even beginning with a love-at-first-sight encounter in a movie theater — evocatively created via shimmery, flickering light effects on the austere merlot walls of a minimalist set by Turner Prize-winning artist Anish Kapoor. But it benefits from the gift of the close-up, particularly as Binoche’s extraordinary face articulates conflicting flushes of feeling that her inexpert dancing, for all its rehearsal-enabled progress, can’t limn quite as precisely. Even without dancing shoes on, Binoche is a seasoned stage performer, but she remains one of the cinema’s great, fearless emoters, best viewed and felt with as little distance as possible: Nearly two decades on the origins of the “In-I” project, this filmic translation feels like a kind of homecoming.